The Competent Heroism of Red Adair

by Bill Canady in PGOS Influencers

September 21, 2023

Competence is knowing what to do, what to do it with, in what order to do each part of it, and then to do it efficiently, completely, and safely. What happens when competence comes wrapped in a person who has the soul of a hero? Meet Red Adair.

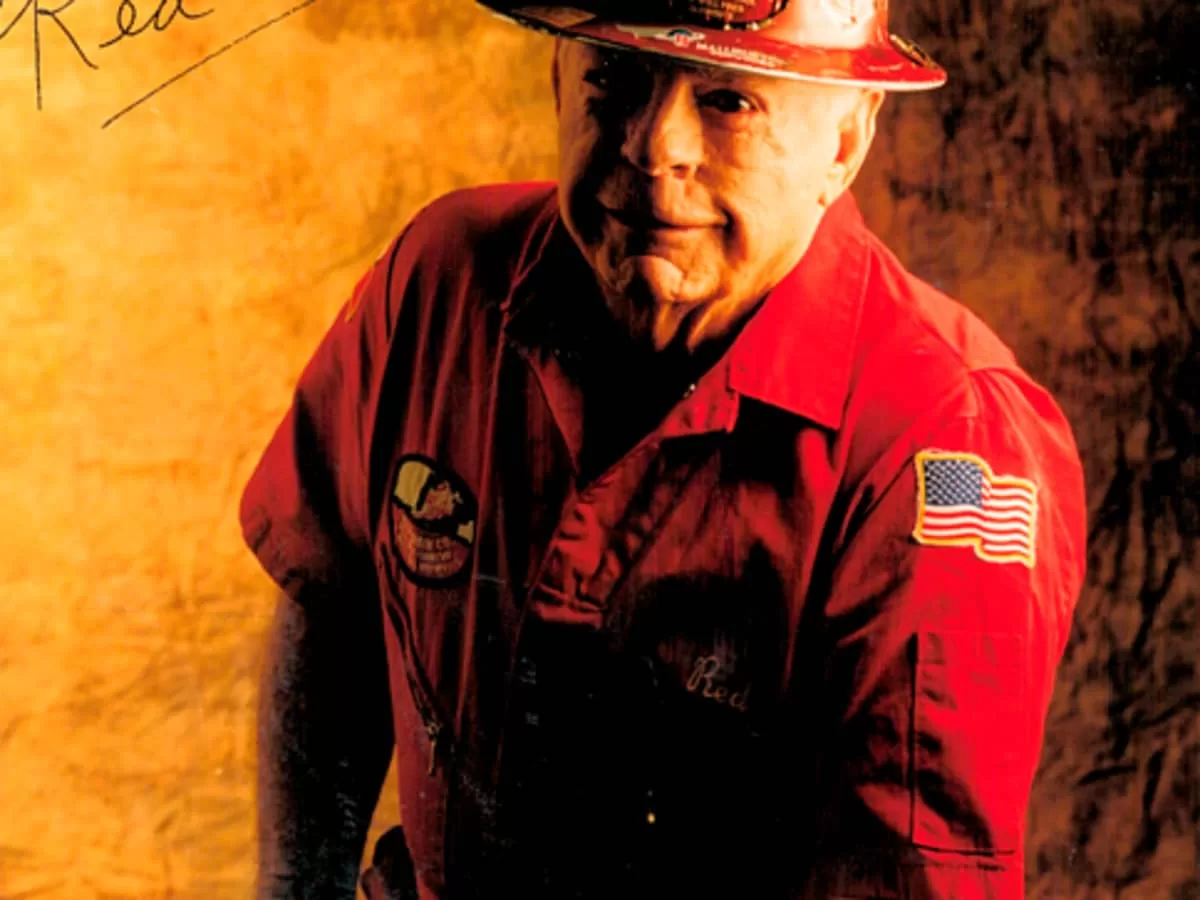

Born in Houston in 1915, Paul Neal Adair was the son of an Irish immigrant blacksmith, who struggled mightily to support his wife, five sons, and three daughters. He did not always win the struggle. From the get-go, Paul stood out among his siblings for his flaming red hair. He would make the most of it. When he could afford new clothes, he bought them all in red, boots included, and when he could afford a car, it was a red one. He became Red Adair.

Adair’s next baptism in chaos came during 1945-1946, the end and immediate aftermath of World War II, when, after being drafted, he served in Japan with the 139th Bomb Disposal Squadron. Rapidly earning the three chevrons and single rocker of a staff sergeant, he learned a lot about disarming duds and controlling explosions and fires. The army assignment gave him a trade and a passion. After his discharge, he returned to Houston and was hired by Myron Kinley, at the time the industry leader in snuffing out oilwell fires and capping wells. He spent fourteen years with Myron Kinley, learning and practicing the state of the art of controlling blowouts and killing fires.

Fourteen years is long enough to call a career, but in 1959, Adair went off on his own. His aim was take everything he had learned both in the army and with Myron Kinley and elevate the state of the art. During thirty-six years running The Red Adair Company, Inc., he led his crews in putting out more than two thousand fires worldwide, on land and sea. He was not above showmanship and branding. He and his crews wore trademark red tin hats, red coveralls, and red boots. They drove red trucks, flew red aircraft, and operated red equipment. But he never had to advertise or ask to be called. When a blowout took flame, the drillers may not have known what to do, but they knew what to say. It was “Call Red Adair.” For nearly four decades, he was the oil industry’s go-to firefighter.

Adair was supremely competent in an extremely deadly profession. There is no such thing as putting out a well fire “from a safe distance.” It must be fought and killed precisely where it is: at the epicenter of the chaos, the wellhead. Most of the time, this requires what seems a wildly counterintuitive if not downright suicidal procedure—the detonation of explosives right at the wellhead. It is a highly effective method of fighting chaos and destruction with carefully crafted chaos and destruction. The explosives have one purpose: to instantly consume the oxygen the well fire needs to burn. Perform this operation both boldly and competently, and the monster blowtorch goes out. Allow competence to lapse, however, and everything instantly gets much, much worse, no matter how daring the attempt.

“People call me a daredevil,” Adair once explained, “but they don’t understand. A daredevil’s reckless, and that ain’t me. The devil’s down in that hole and I’ve seen what he can do, and I’m not darin’ him at all.”[2] When you square off against the devil, you need to respect him because he is infinitely stronger than you are. Still, he can do only one thing, burn. He can do it badder and longer than you can, so your only choice is to respect that fact and deal with it by knowing exactly what to do. The only way to beat this devil is to be supremely competent in engineering the one right way to deprive him of the one thing he needs—oxygen—for the one thing he does: makes fire.

But even when you’ve starved the fire, you aren’t done yet. The blaze may be out, but just about anything can reignite it, explosively. The well must be capped to stop the flow of fuel, whether oil or gas or both, and doing this is the most dangerous part of the mission. Any source of new heat, any hint of open flame, or the least spark will detonate the leaking well and the surrounding area. Because the danger is greatest in this phase, the demand for competence is also at its greatest. No question, Red Adair relished his time out in the dirty, dangerous field. And his employees, colleagues, and clients admired the sense of calm and fearlessness he displayed. They were also grateful for his commitment to safety. Although always in harm’s way, not one of his workers was killed doing their job.

Red Adair respected that devil in the hole, and, despite appearances, he owned up to his fear. “It scares you,” he said, “all the noise, the rattling, the shaking. But the look on everyone’s face, when you are finished and packing, it is the best smile in the world; and there is nobody hurt, and the well is under control.”[3]

While confronting a bad fire was exhilarating, Red Adair devoted most of his time to the continuous improvement of his craft—and not just his craft, but the whole profession of fighting well fires. He had no trade secrets and developed what soon became known throughout the industry as “Wild Well Control” techniques. He added significantly to the tactical arsenal of firefighting. Explosives were always at the core, but to their use were added massive amounts of water and dirt. He used a truck the size of a house to deliver overwhelming quantities of water and bulldozers to move the earth. He designed an array of custom-made equipment, all custom- cast in bronze, to be used in fighting well fires.

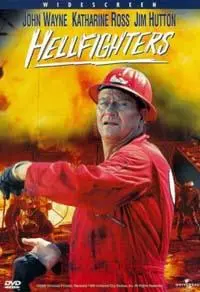

Victory against more than two thousand fires is evidenced by an extraordinary record of lives, property, investments, and natural resources saved. But appreciating the magnitude of the achievement calls for a few examples. In 1962, for instance, he and his crew flew to Algeria and the Sahara Desert to kill a fire that had been blazing for half a year. It was, at this point that such an unwelcome feature of the Saharan landscape had been given a name. They called it the “Devil's Cigarette Lighter.” Its blaze continued unabated, projecting a blowtorch of natural gas some 420 feet into the air—a conflagration sufficiently significant that it was vividly visible to John Glenn as he orbited the earth in his Friendship 7 Project Mercury capsule on February 20-21, and sufficiently hot that it had melted into glass the desert sand surrounding the well. It was a big fire, and Adair calculated the need for exactly 750 pounds of nitroglycerine to yield an explosion large enough to starve even this massive fire of oxygen. Adair’s triumph over the Devil’s Cigarette Lighter prompted Hollywood to shoot a film, Hellfighters, in 1968. It was quite loosely based on Adair’s life, and only John Wayne was deemed star enough to play the lead. Wayne insisted that Adair be hired as technical advisor on the film, and the two became close friends on the set

Adair was called to sea in 1988 to fight the blaze aboard the Piper Alpha oil rig platform drilling in the North Sea, off the coast of Scotland. This one platform produced oil and gas from no fewer than twenty-four wells, and the blowout explosion instantly killed 167 men. Adair’s mission was to kill the fire and cap all the wells. In addition to the blaze and the deep sea, he and his crew were battered by 75-mile-per-hour winds and sixty-five-foot waves.

Three years after Piper Alpha, Adair and his crew were called to Kuwait in the wake of the Persian Gulf War. Saddam Hussein’s army, in retreat, had set Kuwaiti oil wells ablaze. The result was an ecological calamity that many believed would require years to extinguish, let alone repair. On scene, Adair found himself faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles in putting out the fires. He flew to Washington, where he appeared before Congress to plead for funding for more water and equipment. He also needed help securing appropriate medical services for his men and the army’s assistance in removing landmines, which had been thickly sown in the oilfields. From the Capitol, he went to the White House, where George H. W. Bush pledged his support. Adair was given all that he asked for and set about capping more than one hundred wells, an achievement that stood highest among the efforts of twenty-six other teams from sixteen countries. The most optimistic predictions were that the work in Kuwait would require three to five years. Thanks to Adair’s leadership, all the fires were extinguished and wells capped in just eight months. Adair celebrated his seventy-sixth birthday alongside his crew working in Kuwait, and during the period of his assignment there, he and his company also worked in India, Venezuela, Nigeria, the Gulf of Mexico, and the United States killing sixteen other major fires.

“Retire?” Red Adair responded to a reporter’s question while he was in Kuwait, “I do not know what that word means. As long as a man is able to work, and he is productive out there and he feels good—keep at it.”[4] Adair died in 2004, aged eighty-nine. His legacy to the oil industry is obvious, but the example of his career is valuable for anyone who manages or leads a business enterprise. Many qualities, many strengths contribute to success in business, but nothing can long succeed without competence. It is a truth that can be expressed in a single simple equation: Chaos + Competence = Order.

[1] American Oil & Gas Historical Society, “Ending Oil Gushers—BOP,” https://aoghs.org/technology/end-of-gushers/.

[2] The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, “Red Adair to the Rescue,” www.asme.org/topics-resources/content/red-adair-to-the-rescue.

[3] Red Adair, in AZ Quotes, www.azquotes.com/quote/1529#:~:text=the%20noise...-,It%20scares%20you%3A%20all%20the%20noise%2C%20the%20rattling%2C%20the,and%20the%20well's%20under%20control.

[4] Jill Moss, for Voice of America, “Red Adair, 1915-2004: He Put Out Dangerous Oil and Natural Gas Fires Around the World,” http://aitech.ac.jp/~itesls/voa/people/Red_Adair.html#:~:text=In%20addition%20to%20explosives%2C%20the,%22best%20in%20the%20business.%22.