A Zero-Up Menu

August 21, 2023

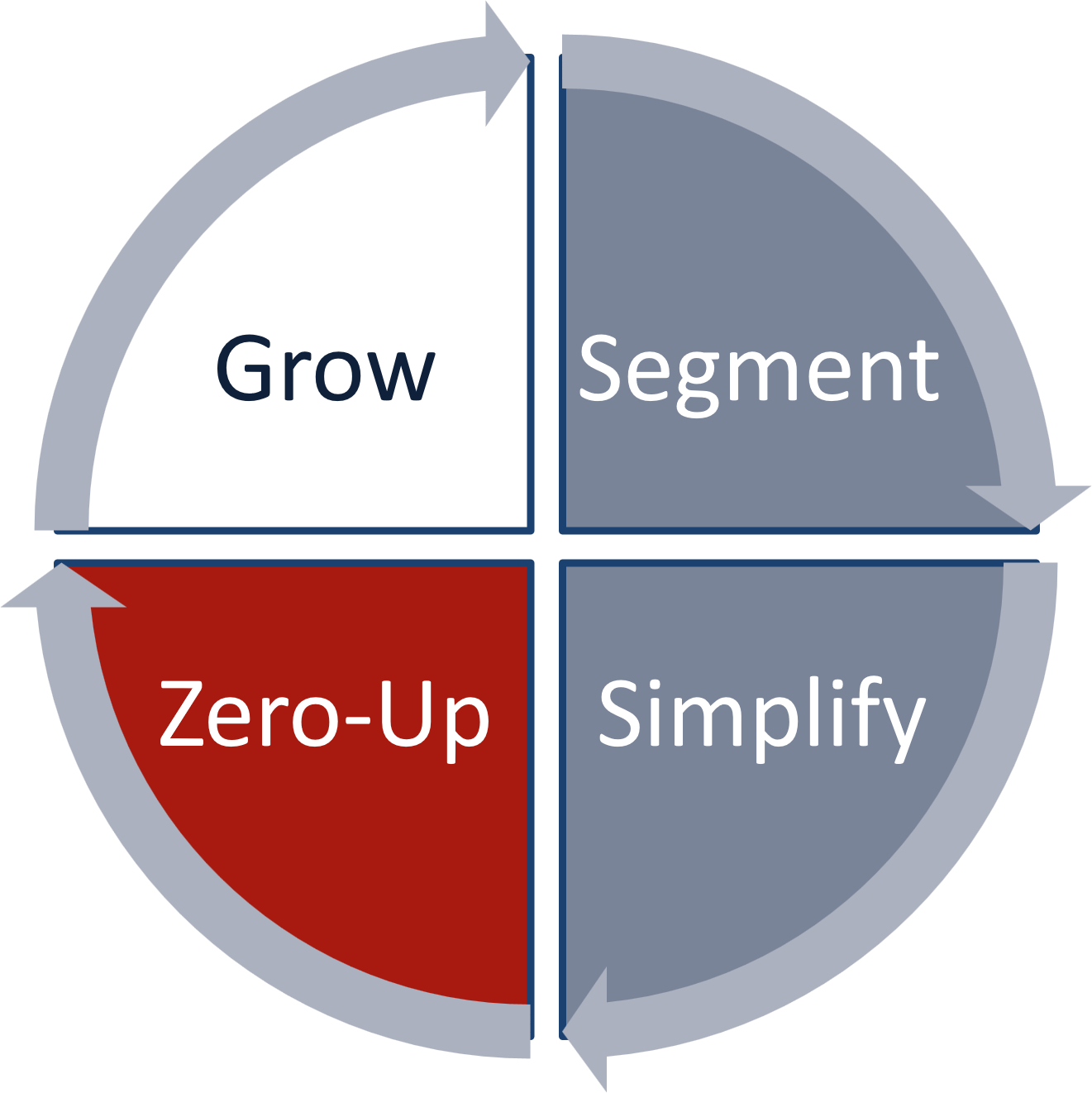

Zero-up offers a robust menu of methods. Which one is best? The answer to this is entirely pragmatic. The right approach is the one that works for you, yielding the optimal view of your business.

The two most widely used zero-up methods are:

1. Zero-up by quad

2. Zero-up by product/customer inflection point

Whichever approach you choose, you will very likely find that 150 percent of your profits are made on the 20 percent of customers/products that generate 80 percent of your revenue. This 80/20 thing is more than a curious truth. It boldly yanks back the curtain to expose the vast volume of resources required to support the 80 percent of customers and products that generate just 20 percent of the revenues. So, take a close look. 80/20 has the force of natural law, but there is no law that says you must support and sustain customers and products that cost you much but give you little or nothing in return.

Zero-up by quadrant

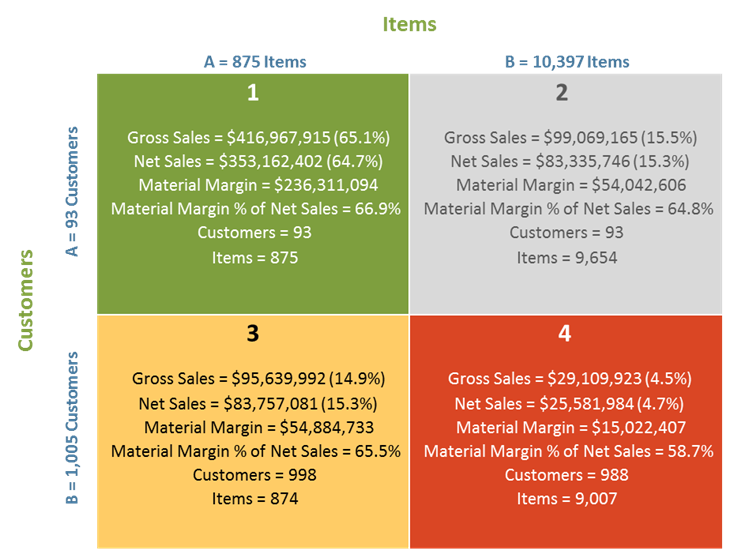

Begin with your most recent 80/20 quad chart. You’ll find a typical one below. Quad 1, at the upper left, represents the top 20-percent of customers (A customers) who buy the top 20 percent of products (A products). In the chart below, this combination accounts for roughly 65 percent of the example company’s net sales. This small number of customers and the products they buy create roughly two-thirds of the company’s revenue. The proportion is typical of most companies.

The other quads here are also typical. Quad 2 shows the 20 percent of customers (A customers) who purchase B products (the lower performing 80 percent of your products). The combination of A customers and B products makes up roughly 15.3 percent of net sales in the example.

Quad 3 houses the top 20 percent products (A products) but joins them to customers from the lower 80 percent. These sales—A products to B customers—account for roughly 15 percent of the example company’s net sales. Finally, Quad 4, at the lower right, contains only 80-percent customers (B customers) who buy 80-percent products (B products). This represents just 4.7 percent of the company’s net sales. Quad 4 is often called the “price up or out” quad because the prices on these SKUs must be raised to a point where sales generate a profit rather than a loss. Those products that cannot be sufficiently priced up must be dropped from the inventory.

Getting going with the Quad Zero-Up process is straightforward. First, focus only on the Quad 1 customers, products, net sales, and material margin. In our example, there are $353 million in net sales, a material margin of $236 million, and just 93 customers and 875 products.

Zero-up by using this data to create (in your mind) a company and a P&L consisting entirely of Quad 1. In this creative daydream, the combination of these A customers and A products are both your only business and the entire business.

Calculate the bare minimum cost required to support this imaginary business. Heap on payroll, variable manufacturing overhead, fixed manufacturing overhead, Selling, General, and Administrative Expenses (S, G & A), and all other attached costs until the operating profit for Quad 1 has been reached. Remember, this is a harmless daydream, in which the entire company is contained in Quad 1, so do not allocate costs based on your real-life company’s current spend, headcount, and P&L. You need to build a P&L from scratch (“zero-up”) based entirely on Quad 1.

The Quad 1 P&L you build will reveal how to optimally run just the business described in this single quadrant. But set it aside for the moment while you turn next to Quad 2 and then Quad 3. Repeat the Quad 1 exercise for each of these, as if each were the whole business. Build a P&L for each, from scratch. You want to determine how such a business would be run optimally; so, for each of these three quads, keep track not only of the spend required but also of the headcount that expenditure funds. When finished, your effort will have produced separate potential optimal future-state P&Ls for Quads 1, 2, and 3, along with the headcount needed to support each.

Now, return to Quad 1, serving just 20 percent of the customers in your current (real, not daydream) company. You will note that the Quad 1 company requires substantially fewer resources and headcount to run optimally than the other three quadrants. The total operating income in Quad 1 is typically 150 to 200 percent of your current total operating income. Take note as well of how the leftover headcount compares to the total number of employees.

This is Quad Zero-Up. And if it seems to you that we have forgotten something—namely Quad 4—you are quite right. We have neglected Quad 4 because we want to get rid of it—unless we can price up the products in this quad and thereby move some of then up to Quad 3.

At this point, what you have is an image of a potential future state. It will guide you in creating a strategy on which to build an executable business plan.

Product/customer inflection point zero-up

The most basic application of the 80/20 Rule is simply to make a set of top-down lists with the highest revenue-producing customer/product combination at the top and the lowest at the bottom. This view almost invariably demonstrates the hard fact that a large fraction of the company’s customer base and product offerings generate inadequate revenue to create profit. No surprise here; it is in line with the 80/20 Rule. While this simple list affirms the validity of the Pareto Principle, it is of very limited practical use in zeroing up. In business, profit, not revenue, is the final measure of success; therefore, we must determine which customers are profitable and which are not. We want to serve profitable customers, A customers, and serve them so well that they become our raving fans. We want to retain them, and we want to figure out how to convert as many of our B customers into A customers. An inflection point zero-up analysis reveals the “inflection point” that separates profitable from unprofitable customers.

Go back to daydreaming for a bit. Imagine you are in charge of a brand-new company. Populate it using your top-down customer list. Take from it your best customer and move him/her to the new (imaginary) company. This done, calculate the absolute bare minimum cost required to support this single customer. Include material costs, variable payroll, variable manufacturing overhead, fixed manufacturing overhead, S, G & A, and other attached costs until you reach the EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) for that one best customer.

Now, move on down to the next customer, the number 2 on your top-down list. Repeat the exercise. When you are finished with customer number 2, repeat the process all the way down to the bottom of your list. You will end up with EBITDAs for each customer as well as a running total. You will find that as customers are added during your descent down the list, the running-total EBITDA for this pristine new company increases at a decreasing rate. Plot this cumulative EBITDA graphically, and you will have a (probably quite lumpy) bell curve. It rises, fluctuates here and there, and then begins to flatten out. At some point, after you add the next lowest customer in line, the curve will plunge, inflecting downward dramatically. It is at this point that the addition of a customer lowers your company’s overall EBITDA. With some exceptions, the addition of each customer after the inflection point is reached lowers overall EBITDA yet further.

Don’t neglect the exceptions to which I just alluded. You may find some customers on the lower end of your list contribute positively to EBITDA, and you may also find some customers higher up on the revenue scale who violate the general rule that the more productive of revenue the customer is, the more profitable. So, just reorder your customers strictly by their individual EBITDA. This will give you a true bell curve, without hills and valleys. Locate the peak of this bell curve. Everything to the right of the inflection point consist of the customers who eat away at your company’s profitability.

As with the Quadrant Zero-Up method, completing the Product/Customer Inflection Point Zero-Up exercise will not change your company. It will, however, provide a starting point for the development and execution phases of the 80/20 process. But take a breath. Don’t fall in love with the curve. It is only a picture, not reality itself. The inflection point you identify should not be used as an iron rule dictating what customers and products to kick out the door. There are other strategies available, which will be covered in other blogs. The numbers, charts, and what-ifs are not holy writ. Thinking is required. But playing the Zero-Up game will give your thinking a sound place to start.